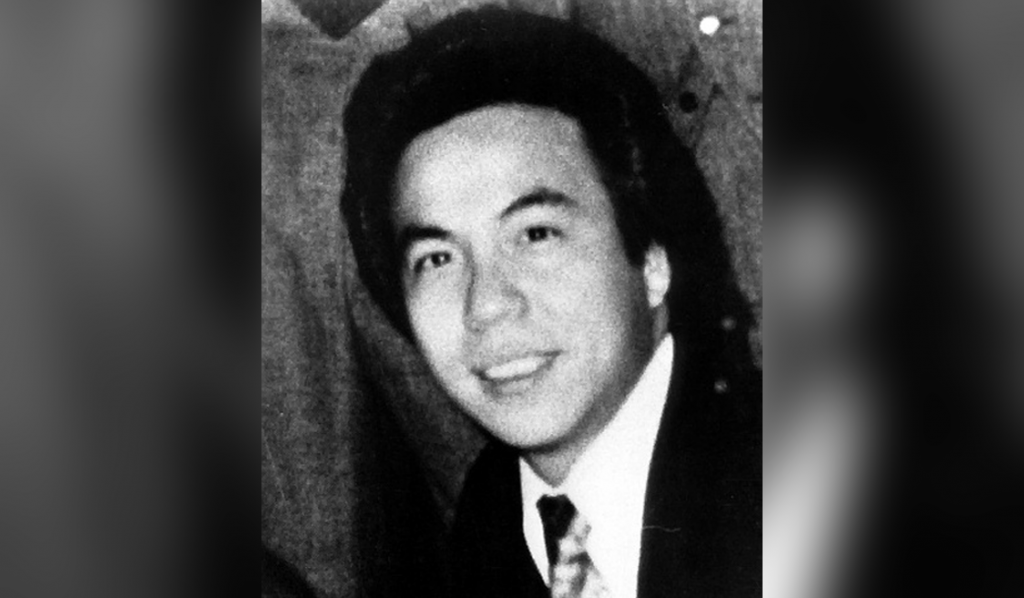

Vincent Chin was 27 years old and about to be married when he was murdered during a time of heightened anti-Japanese emotions. (Public Domain Photo)

Forty years ago, when anti-Asian feelings were on the rise in Detroit’s auto plants, a Chinese American worker was murdered. What role did bigotry and prejudice play in his death?

Since the first workers began organizing, unions have been driven by an urgent need to seek justice and fairness for all. Unions do not come into being just because of outrage: we channel our anger into seeing that individuals are treated fairly and justly. It is what fuels our bargaining and political action. It is a core value of our movement.

There is a legion of examples in Michigan of organized labor meeting struggles and reacting with a demand of justice for all. In Detroit’s Cadillac Square an estimated quarter million workers rallied in 1937 to support sit-down strikers including several hundred female (and mostly immigrant) workers striking for recognition in their cigar factories. And sixty years later in 1997, thousands of trade-unionists from all over the world came to Detroit for two days of rallying to support striking newspaper workers. In 2013, United Auto Workers Local 600 members took to the streets to fight rampant evictions. These days we stand in solidarity with workers organizing at Amazon and Starbucks. We have been at our best when we fight not just for ourselves, but for others as well.

In stark contrast are moments where we fail to live up to these values and ignore the mandates of our movement, or when we stop hearing the voices of the communities that depend on us to be an ally in fighting for what’s right. That is when our values erode, slowly. Examining our failings does not make us weaker or undermine our moral authority. Learning from them is a profound way to find value in our failings and emerge stronger on the other side.

That is why the story of Vincent Chin is important.

In 1982, Vincent Chin was murdered by two men who worked in the auto industry, because they thought he was Japanese and, therefore, the cause of their economic insecurity.

This is what we know from the court case: Ronald Ebens was a superintendent at Chrysler’s Warren Truck Assembly and Michael Nitz was a laid-off Chrysler worker who was also Ebens’ stepson. Vincent Chin was a 27-year-old Chinese American who was celebrating his upcoming wedding with friends.

It was a cool night in Highland Park on June 19, 1982, when the three found themselves at the same strip club. Ebens was heard to call Chin “chink” and “nip” and said to Chin, “[i]t’s because of you little m—f—s that we’re out of work.”

A fight broke out and everyone left the club, but the anger continued. Ebens and Nitz then got a baseball bat from their car and started to look for Chin, offering a stranger $20 to find the “Chinese guy” because they were going to be “busting his head.” They eventually found Chin at a McDonalds, and, after a short chase, Nitz grabbed Chin and held his arms down while Ebens beat Chin’s head in with the bat. Chin died four days later. The two ended up pleading guilty to manslaughter. Neither received jail time.

That is the view if you tighten your lens on just the actions of two racists on a long June night in 1982. But the context around which they acted reveals more.

Trouble in the Auto Industry

In 1982, the domestic auto industry was two years into a deep recession triggered by an oil crisis. Consumers voted with their wallets, and they wanted fuel-efficient vehicles. That meant imports gained market share while GM, Ford, and Chrysler lost theirs. Hundreds of thousands of UAW members who worked at those auto plants were laid off. The federal government estimates that by the end of 1982, 24 percent of U.S. autoworkers had lost their jobs. They saw their contracts being reopened to give companies concessions to keep them afloat.

Their anger was real. But what Ebens and Nitz chose to do with their anger was to transform it into a hatred of a broad category of people.

They did not direct their anger at the employer who failed to anticipate market changes and earn back their market share. As early as 1949, the UAW urged automakers to build fuel-efficient cars, publishing a pamphlet, “A Small Car Named Desire.” Nor at elected leaders who seemed impotent in the face of the double-dip recession.

No, they blamed their demise on an ethnicity and a race: to hell with the fact that Chin was a U.S. citizen, to hell with the fact that he was an industrial draftsman at an engineering firm in the same auto industry Nitz and Ebens worked in, to hell with the fact that they did not know the first thing about Chin other than the shape of his eyes. That was enough to make Chin pay.

Which leads to the next part of this story, which is more diffuse and cloaked in shadow. Were Ebens and Nitz unique in their views? What was feeding their bigotry? Without question, those two men are responsible for the murder of Chin, and it is equally true that others exposed to the same culture as Ebens and Nitz did not murder Asian Americans.

But what incubated that kind of hatred? Who contributed to the conditions? Or more to the point, who stood by and watched the toxic stew of anger and racism brewing without calling it out for what it was?

There is plenty of evidence that there was a significant culture of anti-Asian bigotry in Detroit in 1982. The nightly news featured stories of fundraisers of $1 per swing at a Japanese vehicle as casually as reporting on adoption day at the dog pound. T-shirts, bumper stickers, and posters drove the point home to autoworkers: your economic insecurity is caused by the Japanese.

Some auto plant walls displayed graphics featuring stereotyped buck-toothed Japanese taking American jobs (it is worth noting that this same type of vitriol didn’t get expressed at German Americans, despite growing market shares for Volkswagen, Daimler, and BMW).

Slurs like “Jap” and “Chink” flowed like water on many shop floors. These were not closeted acts of bigotry — they were displayed proudly at Labor Day parades and on t-shirts worn to UAW events. And this hatred was not limited to UAW members — other members of other unions and even auto management joined in bigotry.

Confronting this bigotry is an important part of strengthening union values. We must ask ourselves how this happened. We need to acknowledge that we failed to speak out against the vilification of a people.

It is a conversation long overdue and timely today. The voices of the Black Lives Matter movement are demanding truth and reconciliation with such a fervent urgency that the status quo of yesterday cannot remain. There has been a wave of anti-Asian action driven by the unproven belief that China was responsible for COVID-19. Muslim Americans have been targeted by bigots. And there has been an increase in violence against Jews and their synagogues.

Labor unions cannot be immune from the internal examination of their pasts that other institutions and government agencies are experiencing. But doing so — however difficult — will only prove to be another example of our labor movement honoring its commitment to solidarity.

— Sandra Engle is a member

of UAW Local 2325 (Region 9A) and Director of UAW’s Public Relations Department

Reprinted (with updates) from Michigan Labor History Society, Spring 2022 newsletter

Other users read these articles next…